John Jacob Kreischer and Katherine Gilcher:

Their Story

and Family in Syracuse

and Onondaga County, New York

by Michelle StoneCopyright 2004-2007. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: Passage to a New World (1883)

|

Above, the port of Bremerhaven. Below, a view of the free port (Freihafen) of Bremen/Bremerhaven, and exterior and interior views of the train station (Bahnhof) in Bremen—scenes our immigrant ancestors would have encountered, as they looked in the 1880's. |

|

|

|

On a Wednesday, the 30th day of May, 1883, the massive steamship Elbe of the North German Lloyd line pulled away from the dock in the northern German harbor town of Bremerhaven, port terminus of the city of Bremen (map), to venture beyond the mouth of the Weser River and into the cold green waves of the North Sea. Picking up speed, the ship steamed its way past the Netherlands, through the narrow Strait of Dover, and entered the English Channel, making a brief stop at the port town of Southampton in the center of the southern coast of England. Then the sleek, four-masted vessel put out to sea once more, this time heading west across the wide Atlantic. Its final destination: New York.

In that year of 1883 unprecedented masses of people were leaving their native homes in the German Empire to come to America. But this tidal wave of emigration had been building for over 40 years. One by one, encouraged by letters from friends, relatives, and neighbors who had emigrated before them, and spurred on by the promise of a better life and future for themselves and their children, they would each, individually and for their own reasons, come to make the momentous decision to leave their familiar world and loved ones behind and migrate toward the unknown.

During the three large waves of emigration from the area today known as Germany, in the period 1845 to 1893, an estimated 4.5 million people left. Most of the emigrants at that time came from the areas then known as Prussia, Bohemia, Bavaria, Württemberg, Hessen, and Baden (map). They made their way across their own country, often leaving their own villages or valleys for the first time in their lives, to travel by river, train, horse, wagon, or by foot to one of the great German emigration ports such as Hamburg or Bremen/Bremerhaven (nicknamed “Der Vorort New-Yorks”—“the suburb of New York”). Most of those bound for America aimed for the ports of New York and Baltimore.

In the 1870’s steamships replaced sailing ships on the trans-Atlantic migration routes. What had in earlier decades been a terrible passage of many months entailing risk of disease, starvation, and death, now became a voyage of two weeks. By the 1880’s there were regularly scheduled steamship departures from Bremen to New York, Baltimore, New Orleans, Galveston, and other ports in the United States. Seasickness, poor food, crowded conditions, illness, and mishaps at sea during the voyage still threatened, but by 1883 the trip from the Old Country to the New World clearly held more advantages than risks.

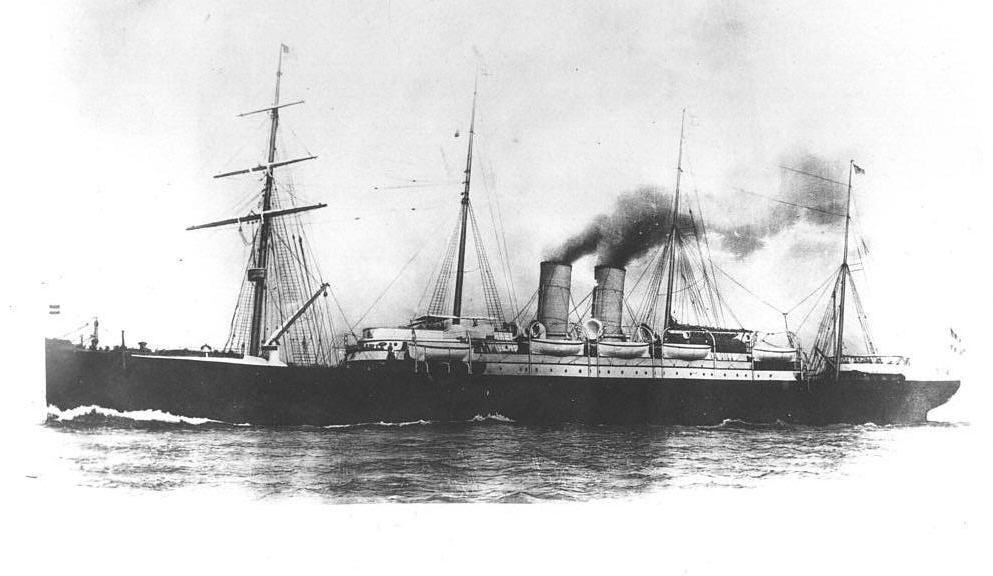

The Elbe was a top-class, express steamship, which had broken all previous world speed records on her second voyage in 1881, when she completed the Southampton-New York route in only eight-and-a-half days. Two years later, in 1883, she was completely outfitted with electricity for lighting. Built in 1881 in Glasgow, Scotland by John Elder & Co. for the Norddeutscher Lloyd steamship company of Bremen, she was a 4,510-gross-ton ship of iron construction, 416.5 feet long and 45 feet across the beam, with four masts and two funnels, and with single-screw propulsion and double-expansion engines providing a service speed of 15 to 17 knots. Aboard the Elbe were accommodations for 120 to 179 first-class passengers, 130 to 142 second-class passengers, and room for 796 to 1,000 third-class passengers in steerage (“Zwischendeck”).

|

The steamship Elbe, built in 1881. Photo used with permission from the Steamship Historical Society of America Collection, Langsdale Library, University of Baltimore. |

|

The famous trans-Atlantic Captain Wilhelm Willigerod of the S.S. Elbe was 44 years old in 1883 when he piloted the Kreischers to America. Nine years later (in November 1892), still a North German Lloyd steamship line captain, he would skillfully keep the S.S. Spree afloat until a rescuing ship arrived, saving the lives of all passengers aboard, including the famous 19th-century evangelist D. L. Moody. |

The majority of passengers on the ship were from Germany. But there were also many citizens of the United States returning home, and non-citizens described as traveling from Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary (representing the growing next great wave of emigrants from the Central European countries), as well as a few from Switzerland, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

In steerage, the men were usually bunked separately from the women and small children. All in steerage traveled under the most minimal and crowded conditions. The food and water provided by the steamship company would be merely adequate, yet this offering represented a huge improvement over earlier decades when travelers brought and prepared their own provisions throughout the voyage or were forced to endure the inadequate, unhealthy, and unpleasant nourishment provided onboard the ship.

Still, space and privacy would have been scant. The trip was a trial, even as it was an adventure. We can only imagine the passage they shared—when the seas were calm and the weather fair, what conversations went on above and below decks; perhaps there was even dancing and music-making—and when the seas were stormy and rough, what misery they must have endured. It would be a life-changing experience for every emigrant onboard, a personal landmark they would never forget for as long as they lived.

Fortunately for the Kreischers the voyage was comparatively brief. Though they traveled in steerage, they had money enough to ride a swift ship. Norddeutscher Lloyd’s steerage tickets on this route cost between $25 and $30 U.S. dollars each in 1883 (approximately $450 per person in today’s dollars; first-class passage cost four times that).

“Heimat”—The Homes They Left Behind

|

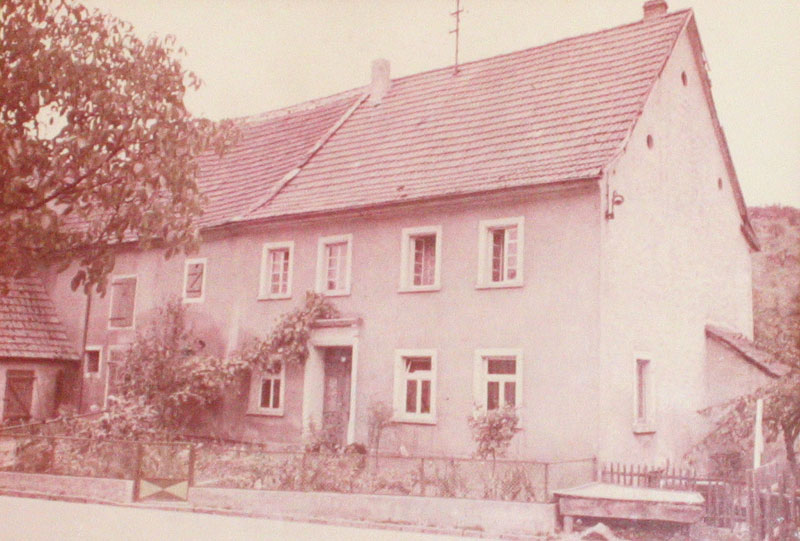

The Kreischer home in Kirrweiler, date of photo unknown (early 1900’s?). It probably looked much like this and was already quite old when Jacob Kreischer grew up there. |

|

|

He was the third of eight children born between 1845 and 1860 to Philipp Kreischer, a farmer (himself born 4 November 1817 in Merzweiler), and Maria Catharina (Allman) Kreischer. The circumstances of the family as Jacob was growing up, and the relationship between them when he left have not yet been discovered and maybe never will be. He no doubt received the standard elementary education available to all the village children at that time and so could read and write, and in some fashion he learned the trades of cabinetmaking (“joining”), carpentry, and farming.

|

Overlooking Kirrweiler (pronounced “KUR-vul-ler”) in its valley in the Pfalz. This was Johann Jacob Kreischer's Heimat. Photo by Jean Claude Kreischer 2007. |

|

Katherine Gilcher Kreischer. Photo taken in Syracuse, New York, date unknown (late 1880’s?). |

The first Gilcher to settle in Rathsweiler had been Catharina’s great-grandfather, Johann Abraham Gilcher (1750-1832), who moved from the nearby village of Oberalben to marry a Rathsweiler girl, Maria Catharina Drumm, in 1778. They lived with Maria’s well-off parents in the largest home-and-barn structure in Rathsweiler, newly erected in 1776 and enlarged a few years later. This Gilcher couple had nine children and the seventh, Johann Peter (known as Peter) Gilcher (1792-1865), Catharina’s grandfather, built in 1828 a one-story house for himself adjacent to his father’s home, and lived in Rathsweiler as a successful farmer in his own right.

|

Catharina Gilcher’s home in Rathsweiler, as it looks today. Photo by Friedrich Hüttenberger 2003. |

In 1846 when Catharina’s parents were married, her grandfather deeded the house to her father—with many provisions and obligations, including the obligation to assume all of the family debts, to take care of his elderly parents, and to let all the other family members live in the house as long as they remained unmarried and childless.

By 1856 when Catharina was born, 15 people were living in the home, including her parents, her grandparents, her four older siblings, and her father’s numerous unmarried brothers and sisters. Conditions must have been uncomfortably crowded. Two generations of large families to support had reduced the Gilchers’ resources, and a series of poor harvests across the country during the 1850’s had driven up food prices and taken an economic toll. The same conditions held throughout the village where a clannish culture prevailed—other relatives, uncles, aunts, and cousins of various degrees of kinship lived in similar fashion throughout Rathsweiler, in the neighboring village of Ulmet (a short walk across the Kappeler Brücke—Chapel Bridge—over the Glan), and in many of the other surrounding villages of Kreis Kusel. This was the Heimat (the home region and culture) into which Catharina Gilcher was born.

Catharina attended the Rathsweiler daily school (Wertstagschule) from the ages of five to 14 (1861-1870), and graduated from the Sonn- und Freiertagschule two years later (1872), receiving a diploma testifying to her “excellent” and “very good” grades and “exemplary” conduct in such subjects as religious education, reading, penmanship, grammar, spelling, written and oral calculation, social studies, drawing, and needlework. This certificate traveled with her to America and would find a home tucked away for many years in the big Kreischer family German-language Bible inherited by her descendants.

|

Rathsweiler, in the valley of the Glan. This was Katharina Gilcher's Heimat. Photo by M. Stone 2003. |

During Catharina’s childhood and school years her father’s siblings moved away from the house, eventually giving Catharina’s family more room. One of her aunts (who was also her godmother), Maria Elisabeth Gilcher (1832-1910), emigrated to the United States in 1857, following the trail blazed for her by her older sister, Luisa (1827-1899), who had similarly emigrated in 1854 (leaving Germany almost immediately following the death of her two-year-old illegitimate daughter). These two women ended up marrying German immigrant men and living out the rest of their lives not far from each other in Wisconsin. A third aunt, Philippina (nicknamed “Binche”) Gilcher (1825-1895), had a son, Ludwig (1857-1892), out of wedlock and moved (around 1860) with him to a small house at the opposite end of Rathsweiler shared with two of her other unmarried siblings, Philipp (1824-1907) and Catharina (1828-1887). The provisions of their father’s contract with their brother Abraham forced these aunts of Catharina’s to move out of their childhood (now Abraham’s) home if they wanted to get married, or once they had children, whether they were married or not.

There were social, cultural, and religious prohibitions against illegitimate births. Shame was attached to them, yet they were not an uncommon occurrence throughout the German lands, for the marriage laws were in many instances cruelly restrictive, requiring that prospective spouses obtain substantial wealth before bonds of romance could be formalized. Non-firstborn children from large families could find it particularly difficult to acquire the needed nest egg. As land grew scarce in the mid-1800’s, many grew up with nowhere to live and no way to afford or earn separate dwelling space. Catharina’s own father, Abraham, and his older brother had in fact been born before their parents married. Many people were middle-aged by the time they wed, and it was not unusual for couples by then to have had several children together, for regardless of the laws, human nature would not wait. For several generations emigration (Auswanderung) had offered one solution as German children came of age and had to decide how to make a life for themselves.

By 1862 Catharina was the sole daughter among three older brothers and two younger brothers, Jacob (born in 1859) and Carl (born in 1862), the youngest. The following year old Peter Gilcher, their grandfather living in their home, died. He would’ve been buried about a mile away in the churchyard of the Evangelische (Protestant Lutheran) Flurskapelle (“chapel in the meadows”) halfway between Rathsweiler and Ulmet, where the Gilchers of the surrounding area had worshipped and been baptized, confirmed, married, and buried since the 1700’s.

|

The Flurskapelle of Ulmet (and Rathsweiler), where the Gilchers worshipped since 1778. Photo by M. Stone 2003. |

Catharina and her cousin, Ludwig Gilcher (her Aunt Binche’s illegitimate son), were contemporaries and no doubt attended school in Rathsweiler together, along with various other cousins among the Drumm, Häsel, Kohl, and Grill families in the close-knit farming community.

1873, the year Catharina turned 17, was an eventful year for her family. In February one of her older brothers, Philipp, died at the age of 24. On the first of May her oldest brother, Abraham Jr., a farmer and barber, age 27, married Maria Mayer in Rathsweiler. On the occasion of this marriage their father, probably affected by the death of Philipp and thinking of security in his old age for his wife and himself, drew up a contract very similar to the one his own father had made at the time of his own marriage in 1846—and thereby deeded the house, the land, and the long-standing family debts to his son Abraham, Jr. and his new wife. Abraham Jr. in receiving this property was bound by the terms of the contract to provide sustenance and space in the house for his parents until their deaths, and for his unmarried younger siblings so long as they remained single and childless.

The following month old Luisa Grill Gilcher, Catharina’s grandmother still living in the home, died at age 75. Within a year or two Catharina’s remaining older brother, Peter, left the Pfalz entirely and went off to make a living as a dyer in Reutlingen in southern Germany. He would later move to Markersdorf, near Chemnitz in Saxony (eastern Germany), where he and the wife he married from that area would remain (childless) for the rest of their lives.

Now for the next several years, by the provisions of the marriage contract, Catharina and her two younger brothers, Jacob and Carl, continued to live in the house with their parents, who lived upstairs, and their older brother Abraham and his wife, who remained childless. They all shared a common kitchen. Younger brother Jacob probably learned his future trade of barbering from his older brother during this time. No doubt everyone had a role to fill in keeping the house, the animals (goats, chickens, and perhaps a cow or two) and what gardens or land they owned by then in proper order. Old Abraham Sr., now retired from the heaviest farming chores, had the time to pursue his secondary occupation of furniture-making and woodworking.

Then documents show that on 15 September 1882, at 10 o’clock on a Friday morning, an illegitimate son named Carl was born to 26-year-old Catharina Gilcher in the home of her parents in Rathsweiler. Mrs. Juliana Graff of Ulmet attended the birth as midwife and filed the birth certificate in Ulmet three days later. A few weeks later, on Tuesday, 10 October, baby Carl was christened by the pastor of the Flurskapelle. Named as baby Carl Gilcher’s godparents in the church record were Abraham Gilcher (the baby’s uncle or his grandfather?), Jacob Gilcher (the baby’s uncle or his great-uncle?) and Catharina Gilcher (the baby’s mother or his great-aunt?). No mention of the baby’s father can be found.

“Auswanderung”—Outward Bound

When Catharina and Jacob arrived at the distant northern seaport of Bremen with the baby the following spring, they had not been legally married. But when the captain of the Elbe filed his passenger manifest in New York City at voyage’s end, there had been sufficient documentation provided to list Catharine Kreischer as Jacob’s wife and Carl Kreischer as his son.

What transpired in Germany in those intervening months as baby Carl survived and grew has yet to be discovered, if it ever can be. As winter settled in and Christmas came and went, as snow covered the familiar red-tile roofs and dormant fields and woods on the hills around Rathsweiler, what was Catharina thinking as she cradled her son in her arms and looked out the window of her parents’ home? How Catharina and Jacob had met, how he came to acquire his trade, the circumstances surrounding Carl’s birth, what their families and friends and the pastor thought and said, how the couple decided to emigrate together, where they got the money, and what steps and routes they took to make their way to Bremen and the sea—these matters can only be imagined for now. What we do know is that, like her aunts before her, Catharina by having a child lost her right to stay in her family home and be supported by her brother. Once again emigration offered a solution to the problem of how to live and where to go.

And this too is known: as the Elbe, filled with crowds of strangers steamed away into the ocean, Jacob, Catharina, and baby Carl were linked together as a family—a family with a common past rooted deep in the Pfalz, but with a long future ahead of them in America. And the very day their ship set sail was Catharina’s 27th birthday. Though their emotions may have been mixed as the boat pulled away from Germany, families, and heimat, they must have recognized that date as a good omen with which to begin a voyage, a fresh start, a commitment, and a new life together.

And so they approached America, and with it a series of new hurdles and choices.

In the previous year, on 3 August 1882, the United States government had passed a new Immigration Act, the first national immigration law applied to all U.S. ports of entry. In effect, the Federal government assumed oversight and control of the rising tide of immigration from the various individual states. The law now explicitly prohibited the immigration of “any convict, lunatic, idiot, or other persons unable to take care of him or herself without becoming a public charge...such persons shall not be permitted to land.” A fifty-cent head tax was also imposed on all arriving immigrants.

As Jacob and Catharina entered New York harbor at the end of their nine-and-a-half-day Atlantic crossing, what were their thoughts and feelings? Were they anxious? Homesick? Excited and exhilarated by the scenes, sounds, and scents around them?

North America’s busiest seaport was a bobbing forest of masts from the many sailing ships at anchor—Bremerhaven and Southampton would have had the same. They perhaps could see the stolid circular fort known as Castle Williams guarding the tip of Governor’s Island. It offered no competition, neither in age, size, nor architectural complexity, to the castles they might have seen along the Rhine, or even to the remnants of their own local Burg Lichtenberg near Kusel, once the largest castle in all of southern Germany. Trinity Church’s steeple towered over the Battery’s skyline, not dissimilar from a hundred other church towers punctuating the city skies of Europe.

But they would have stared at the astonishing Brooklyn Bridge, dubbed “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” officially dedicated and opened to the public just two weeks earlier. It was already considered one of the greatest engineering feats of their century. Did they know it was designed by German-born engineer Johann Roebling?

South Street, the waterfront boulevard filled with maritime-related businesses at the foot of the East River piers, was the first commercial area in the city to be illuminated by electric lights starting the year before. It would have presented a blazing night scene to dazzle anyone used to life in the the rural valleys of the Pfalz. Engineering and science, innovation and scale—these were the distinguishing and novel characteristics of the new world that New York City offered to confront emigrant foreigners.

Two New York City icons that today we take for granted were not yet there in the harbor when Jacob, Catharina, and Carl arrived in 1883. “Liberty Enlightening the World” (the Statue of Liberty) would not appear until the following year, and it would be nine years before the famous Ellis Island immigration center opened (in 1892).

Instead, the 1.4 million Germans who entered the mythical “golden door” of entry into the United States in the 1880’s arrived through Castle Garden, an old fort building on the lower tip of Manhattan that had served as the city’s immigration depot since 1855.

|

The Battery of New York City, as it looked in 1883. Castle Garden, the round building, is center. In the background can be seen Trinity Church’s steeple (left) and the Produce Exchange (far right). |

During the week the Elbe arrived, 11,958 immigrants were landed at Castle Garden, 1,144 of them from the Elbe. On June 9th when the Elbe checked in, New York City was sweltering, with city-dwellers being overcome and prostrated by the heat, and a dense fog filled the harbor in the morning, continuing thick all afternoon below the Narrows. The City of Rome, a steamship of the Anchor Line setting off to Liverpool strayed off course in the fog and grounded itself just before noon in the lower bay. This event probably caused some talk and excitement among the passengers of the Elbe.

An incoming vessel full of immigrants would first anchor at Quarantine Point near Staten Island. Health officials would go aboard to check the ship’s records and search for signs of disease—yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, smallpox. Where disease was found, the ship and cargo would be fumigated and passengers hospitalized as necesssary. A ship that passed inspection would be allowed to dock at its designated pier. Then customs officials would board the boat and go over more paperwork. Wealthy first-class passengers at that point would usually be allowed to disembark and go their ways. The rest of the people on the ship who wished to immigrate (that is, everyone in steerage) would then be ferried with their baggage to the “Landing Depot” at Castle Garden via barges, small steamers, or tugs. This entire process could sometime take days when many ships were being processed at once.

The Landing Depot staff of about 100 officials was hard-pressed to handle the crowds of immigrants by 1883, when those awaiting processing inside the Depot sometimes numbered over 3,000. A cursory medical exam would be given to every individual to weed out the crippled, the sick, the insane, or anyone who might pose a financial burden or medical threat to the city. Then the immigrants would be moved into the rotunda area of the building where clerks fluent in foreign languages would interview them and record their names, nationalities, prior residences, and destinations.

The Landing Depot offered an initial safe haven and some important services to the immigrants, such as a labor exchange, various stores, an information office, a list of registered boardinghouses in New York City, a City baggage delivery service, a registered railroad ticket agent, and an honest place to change their foreign money into American currency. They could meet friends or relatives there, pick up or send mail, or receive money sent to them there by prior arrangement. But once they left the sheltering stone walls of Castle Garden, they were unmistakable—by their clothing, their baggage, their inability to speak or understand English, and their ignorance of the laws and customs of the land—as being green foreigners fresh off the boat. As such they were considered easy prey for fleecing, robbing, cheating, and even waylaying and kidnapping by those swindlers and “sharpers” (in many cases their own countrymen) who lurked on the Battery, just beyond reach of the policemen at the gate.

The vast majority of the immigrants, those with enough money, went west immediately or within a day or so, following the plans they’d made in Europe, or influenced by information they’d learned since their arrival. The daily processions of foreigners and their baggage on their way to the trains was a common observance. Some of the newly arrived Germans intentionally settled in the already well-established German sections of New York City and its suburbs. Others, either through their own miscalculations or by a cruel fate inflicted upon them, found themselves too poor and resourceless to ever escape—these would spend the rest of their lives among the teeming ranks of New York’s poorest slums.

What did Catharina and Jacob think as they stood holding Carl in the crowds at the Landing Depot, back on terra firma, awaiting their inspections and interviews? What did they feel later as they took their first steps outside the Castle Garden walls? Could they understand and speak a few or many words of English? Did they immediately follow the crowds to the trains, or did they head toward a biergarten, hotel, or boarding house? Did anyone meet them at Castle Garden? When they stood face to face with New York City, set free with each other, their three trunks, and with all of America spread out before them, did they know what to do and where to go?

written in 1883, is inscribed

at the foot of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed, to me:

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.

| Chapter 1 Notes |

| Home |